Tag Archives: Cultural Literacy

Affect re-visited: finding the balance between theory and practice

This isn’t really a blog. Or even an essay. More a series of disconnected thoughts arising out of belated readings on affect theory and its implications for Cultural Literacy Research. As a SIG coordinator and consultant to universities on research bidding, I continue to be preoccupied by the impact of ‘the affective turn’ on the social dynamics of definable, site-specific groups in society. Much recent academic and journalistic commentary has drawn attention to the significance of emotion in the formulation of public and private opinion. Amongst other things, it has emphasised the divisive impacts on western societies of populism and collective violence. It has highlighted the disregard of legally grounded democratic principle by autocratic leaders and the nefarious practices of international corporations in the political and commercial manipulation of citizens’ feelings. For many liberal geopolitical commentators, ‘post truth’ has marked the decline, if not the death-throes of liberal democracy.

This awareness has not, however, inhibited the growing influence of ‘affect theory’ within social science itself. In fact, it may well have promoted it. As Ernst van Alphen and Tomáš Jirsa put it in the eloquent introduction to their edited text How to do things with Affect:

“When I hear the word affect I reach for my Taser. An unfair reflex, I know, but affect seems to me a prime medium of ideology today— an implanted emotionality that is worse—because more effective—than false consciousness”

Foster 2012 [1]

The comment was voiced live ten years ago by the art historian Hal Foster in a recorded roundtable on Art and Architecture. Van Alphen and Jirsa for their part were using it as a rhetorical counter-argument to their own polemical objective, namely to devise a method which enables ‘affect’ to be evaluated in ‘operational’ rather than primarily conceptual terms. In their words:

“Rather than providing definitions of what affects are (not), we find it more useful to focus on what precisely affects do, how they operate within aesthetic forms and cultural practices”

Van Alphen and Jirsa 2019:1 [2]

Evidently they were fed up with philosophical debates about the nature of emotion, its relationship to knowledge and understanding and the recent preoccupation with affect as a culturally constructed process. Their formulation chimes well with the goal of the SIG ‘Cultural Literacy and Social Change’. As probably overstated on the CLE website, the so-called ‘Culture SIG’ focuses on the link between cultural theory, literacy in the widest sense and tangible social outcomes. Whether you like it or not, ‘affect’ in its various iterations then presents itself alongside economics, politics and history as a core factor which cannot be overlooked: not simply because it has become modish in academic circles to turn to Deleuze and Guattari and others as an explanation of what has happened to Western Culture since the 1970s[3], but because the impact of the ‘affective turn’ has become such a palpably real aspect of mediated social behaviour. Its consequences are felt in different ways in different locations at different levels of society, but in almost all cases as an accessible response to widespread insecurity and uncertainty about the future.

In the face of overwhelming geo-political complexity and the apparent failure of the neo-liberal system to resolve global economic issues, one reaction on the part of social analysts has been to focus on the local rather than the global, to review the relationship between everyday life in community and the types of cultural activity likely to promote positive change at the micro-level through closely targeted research. Money is short. Practice-led research is under scrutiny. It remains the poor relation of fundamental, scientific investigation and the methodological principles which go with it. As is now widely acknowledged, the response from policy-makers is to encourage ‘co-participation’, viz. the active involvement of ‘ordinary people’ in socially grounded ‘research projects’, projects which raise the profile of their medium-term contribution to the ‘quality of life’ within and between the social groups of which they are part. Such a focus immediately raises questions about the relationship between the empirical observation of social practice and the theory which underpins it. If practice is to be ‘informed’ by theory, on which theoretical school should it draw? Or, to put the question differently, how should different theoretical approaches be most effectively combined in order to offer the most cogent blueprints for cultural action.

A fundamental axiom of ‘Affect Theory’ is that the attempt to drive an epistemological wedge between ‘emotion’ and ‘reason’ is not tenable in practice. As the pre-romantic, agnostic writers of the European Enlightenment amply demonstrated, cognition itself depends on sentient processes which link mind and body. By extension, relations between individuals and groups are themselves ‘embodied’ through the internalisation of shared experience. The recent extreme version of the latter principle underpinning affect theory holds that close intra-group associations are ‘pre-lingual’. Philosophically as well as physically, feeling precedes thought.

Logically, for non-believers in Freudian, Marxist or Behaviourist explanations, or indeed informed sceptics in general, the motivational essence which fuels the mechanisms of inter-personal dynamics escapes objective identification. It has to be felt before being ‘captured’ and thence communicated to others in symbolic terms, eventually to become collectively internalised as ethical, religious or ideological principles.

That symbolic ‘capture’ may be abstract and extremely sophisticated – witness the digital algorithms which structure communication within institutions, minutely categorise our behaviour and manipulate our collective emotional responses to experience. In everyday life on the other hand, the affective dimension is best manifested through language or, sociologically speaking, situated discourse whose ‘frames’ or ‘activity types’ operate as inter-modal cultural lenses combining music, physical performance, spatial architecture and material artefacts of all kinds. Following Deleuze and Guattari’s use of the term ‘agencement’, Slaby et al. refer to their conceptualisation of local relationality as ‘affective arrangement’:

“Affective arrangements are heterogeneous ensembles of diverse materials forming a local layout that operates as a dynamic formation, comprising persons, things, artifacts, spaces, discourses, behaviours, and expressions in a characteristic mode of composition and dynamic relatedness. Our approach facilitates microanalyses of affective relationality as it furthers both an understanding of the entities that coalesce locally to engender relational affect, and also the overall “feel,” affective tonality or atmosphere that prevails in such a locale. The proposed concept is an analytical tool—provisional and open-textured yet sufficiently determinate—to help researchers get a grip on complex inter- or intra-actional settings in which affect looms large.”

Slaby, Mühlhoff and Wüschner 2017:2[3]

However, from Rousseau through Vygotsky and Piaget to Froebel, Schutz and beyond, it is clear that ‘affect’ is much more than a state of mind. While in strictly clinical or philosophical terms, it may be said to precede action or even rational thought, once engaged, it becomes ‘activity-led’. Ideally, affect and activity enter into a virtuous circle which by definition extends beyond the individual, one in which group interaction is necessarily involved. It follows that the first challenge confronting the would-be ‘ethnographer of affect’ is to identify the salient everyday activities which constitute the ‘cultural glue’ of communities and closely to examine the processes by which these are symbolised and collectively represented. To that extent, the development of cultural literacy on the part of citizens and researchers alike becomes an exercise in social geography, designed to reveal the affective chemistry of belonging. The attempt to define this chemistry in national terms very quickly leads to stereotypes which for far too long have afflicted the study of intercultural communication. One striking aspect of pluralistic social fragmentation is that the insignia of ‘affective salience’ filtered through language and behaviour are increasingly context-specific and local in character. They need to be understood accordingly, on their own terms and in relation to each other by using the same heuristic instruments across the local board.Most of the above is blindingly obvious in principle. The problem comes when seeking to apply it in practice, most especially in finding ways to identify and evaluate the affective determinants of social connectedness in terms which are meaningfully communicable and theoretically coherent. All too frequently, the impressionistic, meta-discursive store of hyperbolic adjectives and fanciful metaphor quickly runs dry, to the point where in extreme cases the self-referential, reflexive style of affective analysis runs the danger of defeating its own object by simply replicating itself. Which is why of course, data and creative artefacts relevant to capturing the affective forces which bind and separate groups in society should emanate authentically from the voices of real people interacting in real-life situations. Such a move inevitably changes the role of the soi-disant ‘researcher’ who then becomes a creative yet critically responsible facilitator or mediator who gives meaningful voice to others rather than a scientist seeking empirically to demonstrate an anticipated truth. Thereby, researchers are agents in a catalytic process which enables cultural literacy to define itself.

The epistemological challenge which this discursive double-bind represents for researchers is addressed head on by the exploratory work of the Collaborative Research Centre (SFB 1171) Affective Societies at the Freie Universität Berlin. In fact, the main object of this blog is to draw colleagues’ attention to the clarity of exposition brought to the Centre’s on-line publications. Not only do the group’s outputs retrace the historical development of the relationship between thought and emotion derived from the work of Spinoza, Nietsche, Bergson and latterly Deleuze and Guattari, Nancy Fraser, Judith Butler, Sarah Ahmed, Brian Massumi and others; they also consider in a series of essays the impact of their legacy on current political culture.

The Berlin Group’s collective goal is to illustrate what is meant by the phrase ‘affective relationality’ when it is translated into real-life contemporary examples. It addresses such questions as the extent to which it is possible to reconcile antagonisms within and between specific social groups. As the quotation above illustrates, it highlights the need to identify material environments which foster ‘agencement’, that is sites where dynamic, embodied expressions of feeling can lead to new and sustainable affective formations: not of course for their own sake but as part of a network of activities involving different agents whose diverse outlooks and interests within a bounded local environment are complementary to each other in economic as well as in civic terms. Profuse examples of this kind exist in highly diverse contexts, despite the setbacks of the last two years. They should be identified, critically mediated and their ingredients more widely disseminated by independent research associations such as CLE so that their social and cultural benefits can be shared. I hope that the different case studies coordinated by members of this Special Interest Group will go some way towards meeting that objective.

Robert Crawshaw, 6th April 2022

References

See below a small sample of recent papers on ‘Affect’ published by members of The Collaborative Research Centre (SFB) 1171 ‘Affective Societies’ at the Freie Universität Berlin, funded by the German Research Foundation/Deutsche Forschungs Gemeinschaft (DFG). The papers can be accessed directly by clicking on the titles.

| The Politics of Affective Societies. An Interdisciplinary Essay – Hauke Lehmann, Jonas Bens, Gabriel Scheidecker, Gerhard Thonhauser, M. Ragıp Zık, Aletta Diefenbach, Dina Wahba. |

| Introduction: Affective Societies – Key Concepts – Jan Slaby. |

| Relational Affect: Perspectives from Philosophy and Cultural Studies – Jan Slaby. |

| Emotion, emotion concept – Christian von Scheve, Jan Slaby. |

[2] https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004397712_002

[3] Gilles DELEUZE and Félix GUATTARI L’Anti-Œdipe: Capitalisme et Schizophrénie (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 1972/1995)

[4] Jan SLABY, Rainer MÜHLHOFF and Philipp WÜSCHNER ‘Affective Arrangements’ in Emotion Review, 2017 p.2

Holding on to Wonder

ARTIST BLOG | HANNAH FOX

Being asked to write a short piece about ‘Your Life as an Artist’ is a curious task.

I remember messing around with setting up my first smart phone and being briefly puzzled by the face of the scowling woman looking back at me. There was a full couple of seconds before I realised that ‘selfie’ mode was engaged and the woman I held in my hand was me. Unconsciously observing myself was depressing in a mortal kind of way but also rather revealing in a vital way. As an Artist I spend pretty much all of my time, headspace, imaginative energies and practical efforts looking out at others. At other peoples’ communities, moments and needs and I respond outwardly to those things. For these few hundred words, though, I will turn the mirror of the selfie back on to observe and articulate who the Artist is ( it’s me..) and how, when, what, where and most importantly why, the Artist makes her work.

I am nearly 50 and I have been a working freelance Artist all of my life. I grew up in the 1970’s ‘on the road’ with the legendary collective of artists Welfare State International. My parents, John Fox and Sue Gill , along with many others, led this wild and evolving band of musicians, performers, dancers, pyrotechnicians, sculptors and writers. I was a quiet little girl who helped a lot. I sat under the table during meetings, collected scraps of offcuts and made my own costumes, joined in the loading of the trucks, learned my parts on the drum or the trumpet, knew my lines, my cues and set my own props. This was expected of everyone and not a big deal. We lived in caravans and toured the World making work in communities, creating wonder and sometimes trouble, giving, teaching and usually leaving behind a creative impact in the communities we visited in the form of memories, community connections, tangible skills, stuff and inspiration.

After settling in a Northern English town and finally attending ‘proper’ school ( which in itself helped to form me in distinctly different terms) I studied Fine Art at Glasgow School of Art in the beautiful, delicate and now fire devastated Mackintosh building. Dogtroep came to town, a similarly wild band of Dutch creative artists and they made a massive rambling theatre show, Camel Gossip, in the Tramway building when it was still a semi derelict tram shed full of stinking puddles and pigeons. They were seeking a few local artists to get involved and so I joined them. Again, I witnessed extraordinary and surreal art at work crafted by dreamers and makers who worked incredibly hard and knew their stuff. ‘Wonder’ seemed to be their staple and they had developed methods and approaches that were robust and practical to reliably conjure the wonder night after night to audiences of hundreds. These artists were not afraid of magic and they took it very seriously. This epic show formed another formidable apprenticeship for me.

After this immersive, invigorating and terrifying ‘placement’ I was asked by the Artistic Director to join their company in Amsterdam. She knew ‘I got it’ and worked hard. I understood that washers and rivets were as important as wigs and solos and I was tough. I ran away with Dogtroep for 5 years of International site specific performance.

It’s worth spending so many words on these origins because it is fundamental to who I am and my methodology as an Artist. I continually hone my craft, in whatever art form I am utilising, to structurally and reliably hold the wonder for others. It’s often a fragile thing, fleeting and surprising so it’s important that it doesn’t fall down. Badly held or broken magic is worse than no magic at all.

I work across many art forms making public work; films, digital animations, projections, theatre shows, installations and constructions. I utilise whatever art form best suits the idea, the context, the purpose and the budget. I am commissioned to work Internationally, both inside and out, sometimes on my own, but often pulling teams of other artists together who bond their diverse skills to create a more complex work. Sometimes budgets are massive, sometimes tiny. I am asked into settings; a community, a landscape or a conundrum that needs an artistic response, process and outcome. I meet, talk, draw, listen a lot, ask many questions, look around the back, talk to the people up the road, think, sit and dream and then I know what is needed and what I can do. I don’t call myself a Community Artist but an Artist who works in context. This response might be designing and building an interactive installation for hundreds of families to experience at a free festival, working within a community to craft and tell the stories of their estate or village or animating a set of fairytale films about resilience, fear and hope for children to access and explore with activities during the Covid 19 crisis lockdown.

All the work I make has a purpose and I tether the art tightly to the purpose. The purpose shapes the work and the art must respond and bend to the how, when, what, where and why. The art is the tool to fulfill the purpose and, although it is free to soar in surprising directions, it must always serve the purpose, for responding with care to the context, the job in hand, is the work. My role is, in many ways, simply to hold the space.

Having taken this selfie and probed at my practice to briefly describe it on ( digital) paper I can recognise that my work is direct, daringly simple. It seeks to be connected, meaningful and beautiful, welcoming in participants rather than spectators. It endeavours to be playful and imaginative, to make an impact where it matters, to frame a different perspective with depth and honesty and most especially, during these terrifying times, to hold on to wonder.

both now experimental and successful artists and musicians.

Photo: Lizzie Lockhart.

50 year old Hannah creating a Fairytale touring show for

Northumberland with November Club.

Photo: Jason Thompson

Cultural Literacy and Public Art in a Global Pandemic

Introducing Pippa Hale, Artist

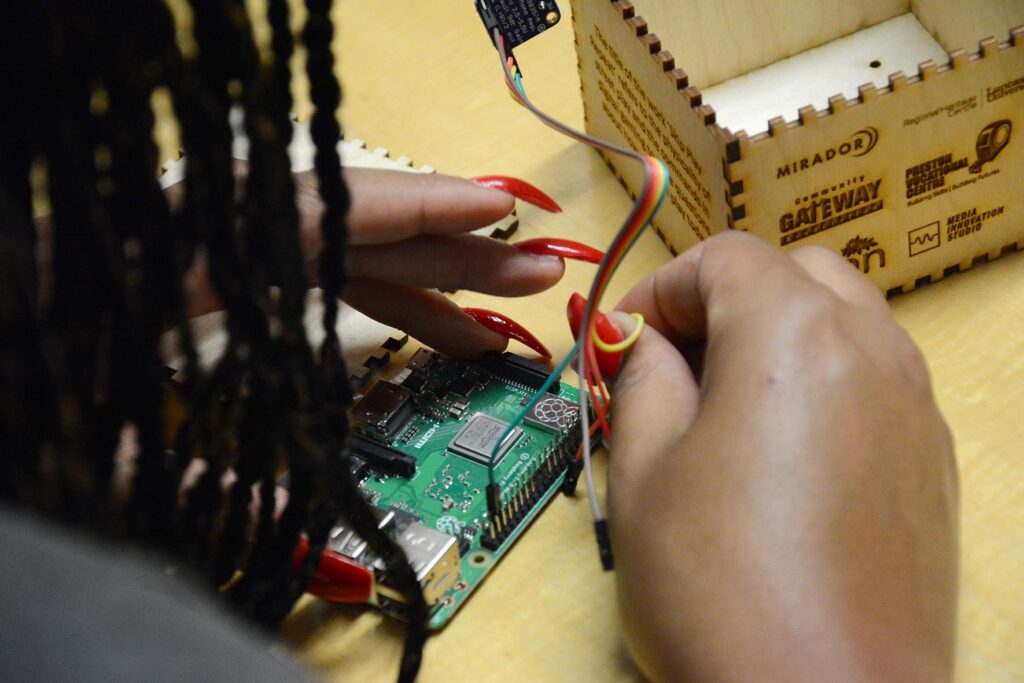

I was fortunate enough to encounter Pippa Hale’s work through the Special Interest Group’s case study of the project ‘Walking in Others’ Footsteps’ run by Mirador Arts, a highly active, charitable Community Arts Trust based in the North-West of the UK. The sub-project for which she was responsible was called ‘Skip, Play, Repeat’

‘Skip, Play, Repeat’ involved re-enacting street play activities of previous generations of children by recrafting the artefacts which were commonly used at the time. Children of all backgrounds from schools in Preston took part in outdoor events in which they learnt how to master the special skills demanded by the newly refashioned ‘toys’. But this was only the start. An extensive interview with Pippa for the case study and a visit to her website bore witness to the range of her creative vision and to the impact her recent work was having in the Leeds area.

Many professional artists who rely on commissions and externally funded cultural projects to further their contribution to community wellbeing find themselves constrained by the cutbacks in local government support, party political interests and the priority given to large scale economically driven projects which are dependent on the private sector. Other drawbacks are the limited timeframes of funded initiatives whose sustainability UK Research and Innovation and The Arts Councils have only recently begun seriously to address. And then there is the small matter of COVID 19.

How would leading artists such as Pippa survive the present crisis?

Her varied work in sculpture, installation, co-curation and infrastructural initiatives such as the establishment of prizes and new cultural venues was beginning to make real inroads into the Leeds environment. Like other self-driven, multi-talented, entrepreneurial artists with a strong sense of mission, she was clearly a core catalyst in the cultural renewal of the City. Her personal blog below gives a sense of the challenge facing her and others like her. It is an aspect of cultural literacy which will be explored in greater detail in subsequent entries on this site and elsewhere.

Pippa’s Blog

Cultural Literacy and Public Art in a Global Pandemic

Being an artist is a struggle at the best of times, but the Covid-19 global pandemic is having a devastating effect on the cultural sector, the ramifications of which will be felt for generations.

I’m a contemporary artist who works with heritage venues, galleries and in the public realm, making works that respond to the history, people and geography of places. Since having kids of my own, I’ve also become interested in play and its correlation to creativity. Projects are commissioned by local authorities, museums, private companies, educational institutions and arts agencies and have included works in sound, film, events, iron, found objects and foam. Sometimes the works are permanent, sometimes they are temporary, but the overall narrative is about rooting artworks to their location, connecting people to their history and place and each other.

Issues confronting artists working on public projects / What are main challenges professionals in my position have to face?

Being an artist, no matter what your practice, is a challenging career choice. Whilst it can be enormously rewarding, it necessitates incredible amounts of self-discipline, chutzpah, humility, persistence, resilience – not to mention creativity. At no time is this more true than when working in the public realm. Whereas galleries have experienced staff who support the presentation and dissemination of contemporary art, public art can be commissioned by multiple partners who perhaps haven’t worked with artists before.

The impetus to commission works of art for the public realm are varied, but are often political. Artists are often brought in at a time when places are undergoing change and artworks are commissioned to smooth the planning process or to sweeten local communities.

Maquette for Ribbons, a new sculpture celebrating women in Leeds Photograph: the Artist

Hardwiring the tech on the tops and whips Photo: Darren Andrews, courtesy of Mirador Arts

Participant with top and whip she’d handcrafted, hard wired and programmed Photo: Darren Andrews, courtesy of Mirador Arts

What kind of contribution does my work make to the ‘cultural literacy’ of communities?

One of the first things I do when working on a new commission is to connect with people in the local area. I never assume they have an interest in contemporary art, but I know they are passionate about the places in which they live and work. Talking to them is crucial when trying to get to know a new place as it builds up a personal picture of somewhere that is based on memory and local networks rather than the official stories recorded in regional archives. I can get a deeper understanding of how that community and its culture interact and it’s those conversations that ultimately inform the artwork.

At the end of the day, I’m making a new thing for that place, be it an object or an event, something that will simultaneously connect contemporary communities to the past and to current debate.

I believe good public art is essential because it reflects who we are as a society, our values and beliefs, our pasts and presents and adds depth and meaning to our cities, towns and villages. In recent weeks, public art has been at the forefront of contemporary debate with the toppling of memorial statues in Britain and the USA. Now, more than ever before, public art has an important role to play in defining who we are a people, a society, a nation. Now is the time to be commissioning new works of art to reflect these times and to provide a legacy for the future.

Unfortunately, this moment is happening during a global pandemic where arts funding for new projects has been shelved as public and private bodies redirect their funding to meet the immediate financial needs of arts organisations. And of course, we hardly dare imagine what that new landscape may look like, let alone ignore that niggling worry that these funding streams may never come back on line.

Dealing with these issues as the future unfolds is a topic I hope to be able to discuss publicly: through the medium of this website, as well as through workshops, presentations and other fora which build on what has already been achieved, not only in Leeds but elsewhere in the UK and abroad.

Pippa Hale, Leeds

June 2020

Playing with a hoop and stick Photo: Darren Andrews, courtesy of Mirador Arts