Category Archives: Cultural Literacy and Social Futures

Conversations

Conversations is a new series focusing on the interaction between artists and social environments. It builds on an earlier blog by the Special Interest Group ‘Cultural Literacy and Social Futures’, linked to an Arts Council funded project on behalf of Clifton Park Museum, Rotherham entitled ‘Revealed Roots, Concealed Connections’:

The blog described how, in August 2021, British government’s policy on the function of museums had changed over the previous decade. Rather than viewing such institutions as essentially publicly funded with the objective of preserving archives of historic interest to be viewed by an indeterminate, metrically monitored visitor base, The National Museum Directors’ Council (NMDC) https://www.nationalmuseums.org.uk/ acknowledged the diverse character, size and relative national importance of the institutions for which they were responsible. Apart from promoting virtual access which would enable greater flexibility in the way artefacts were made available to a wider public, the NMDC’s 2021 report ‘Museums Matter’ stressed regional museums’ civic role as physical hubs.

According to the report, museums were to become social centres which reflected the everyday lives of people in local neighbourhoods. They would reinforce their identity as active citizens by increasing their sense of belonging to mutually imagined spaces. They would cause people to think more deeply about the meaning of their daily existence in a way which would not simply increase their stock of knowledge but be self-fulfilling to people in practical terms as members of a wider community. In short, the 2021 NMDC report was urging museums to develop levels of cultural literacy amongst groups of different types and in so doing to promote shared understanding.

https://www.the-liminal-space.com/all-projects/museums-of-the-future

The NMDC report went on to say that smaller, municipally based, regional museums should be less dependent on public resources. Arts Council funds were being cut back. Museums should be more autonomous in their operations. They should involve the public more directly in exhibition design and curation. They should be more open, less static and inward looking, more demonstrative of the present as a dynamic reflection of the past through more creative, more activity-led access to their archives. Their physical spaces should be more readily accessible for hands-on activities which brought people together as memorable expressions of their day to day preoccupations. This policy initiative has since been vigorously followed through. As the Museums Association on behalf of The Esmé Foundation now puts it

‘Overwhelmingly, our research has revealed a desire for a fundamental shift away from thinking of museology as strictly linked to place, space and assets, towards an emphasis on how these elements create meaningful and sustained interactions with people and communities.’

Against a background of economic stringency, serious effort has since been made by The Museums Association and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) to address a number of core questions. These questions have arisen in the wake of the pioneering work of François Matarasso[1] and the game-changing Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) report compiled in 2016 by Geoffrey Crossick and Patryzja Kaszynska[2]. How should local institutions go about enabling local people to realise creative potential they didn’t know they had to the benefit of the community as a whole? How should improvements in the quality of their life experience be satisfactorily assessed? Where does museums’ responsibility for promoting social change begin and end? What are the financial implications for smaller municipal institutions, borough councils and their related centres of learning if they are to meet the challenges just outlined? What should be the role of university-led research in making sense of the interrelationship between economic planning, demographics and the civic value of culture at the individual and collective levels? An inevitable tension continues to exist between economic priorities and civic well-being, one in which local government departments, developers and party political interests are pitted against each other at the expense of projects which are part of integrated, collaborative, and above all sustainable strategies.

At the time of writing, the UK Department of State responsible for the funding of museums and galleries: The Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) strongly emphasises technological development as a key element in the growth of the so-called ‘creative industries’

https://www.ukri.org/news/ukri-launches-digital-innovation-and-engagement-fund-for-museums/

Interactive gaming and instantly communicable mediatised performance have become inexpensive, ready-made, creative vehicles in which individuals have control over their cultural output alongside existing archives. Museums, Galleries and other local cultural spaces represent accessible venues in which such outputs can be physically rehearsed and displayed as collaborative events. However, they demand technically trained personnel, appropriate equipment and new forms of curation if such products are to be supported to best advantage. While many might argue that they detract from the personal and social enrichment afforded by real life experience, the obvious compromise is to seek a creative combination between the two.

Stakeholders at every level are aware of the complexities and financial constraints involved. ‘Co-participation’ and ‘Engagement’ have become watchwords of policy initiatives governing funding by national agencies in the UK such as DCMS, the national Arts Councils, and UKRI, charitable organisations such as The Esmé Fairbairn Collection, The Rowntree Foundation, and larger grant-awarding agencies such as The Leverhulme Trust. Under the aegis of the recently established Centre for Cultural Value (CCV), guidelines have been posted which spell out in detail what makes for effective practice-led research carried out by universities in collaboration with local agencies:

https://www.museumsassociation.org/app/uploads/2020/06/28032017-museums-change-lives-9.pdf

At the level of national media, much is made of popular spectacle: choral singing, ballroom dancing and cookery competitions, gardening, and craft repair. Such immediately recognised manifestations of popular culture are complemented by fragmented on-line, mostly privately initiated networks funded by subscription which focus on reading, writing, music-making, drawing, photography, drama, dance, rambling and so on. Festive ‘events’ attract crowds. On the other hand, institutionally embedded, externally funded projects reach out to local communities on a more ambitious yet more focused and less expensive scale. Associations such as the Centre for Cultural Value, the National Council for Cultural and Academic Exchange, Cultural Literacy Everywhere and Liminal Space offer platforms featuring case studies for what is now a burgeoning field.

Notwithstanding these trends in academic and cultural policy, the incorporation of professional artists into local cultural projects continues to encounter serious obstacles. Much space is given to top-down cultural agendas which have attracted global media as opposed to practical deas which emanate from local people themselves. For the latter to have lasting leverage, it is normally necessary for artists working on commission to collaborate with members of the public. Their mission is typically to translate existing aspects of daily life into artefacts which literally take on iconic status and become part of the social and economic fabric. In this environment, ‘art’ is more than a pastime which fosters a sense of well-being. It is a catalyst where social practice itself becomes a work of art, one in which artists are themselves socially engaged and are given a key role as cultural coordinators by local political institutions.

The purpose of this series of ‘conversations’ is to give voice to the experience of artists who have taken the initiative to co-ordinate collaborative work of the kind just described. The environments in which they have operated in the recent past are different, as are the types of activities which have emerged as potentially iconic. The nature of the collaboration differs too, as do the institutions with which the artists work. The main issues, however, are endemic: sustainability of impact, access to funding, internal political priorities, functionality of space, legitimacy of roles and relevance. It is to be hoped that the artists’ commentaries will shed further light on the potential dynamics and long-term outcomes of practice-led research.

Robert Crawshaw

[1] François Matarasso A Restless Art (London: Gulbenkian Foundation, 2019)

[2] Geoffrey Crossick & Patryzja Kaszynska Understanding the Value of Arts and Culture (London: AHRC, 2016)

Affect re-visited: finding the balance between theory and practice

This isn’t really a blog. Or even an essay. More a series of disconnected thoughts arising out of belated readings on affect theory and its implications for Cultural Literacy Research. As a SIG coordinator and consultant to universities on research bidding, I continue to be preoccupied by the impact of ‘the affective turn’ on the social dynamics of definable, site-specific groups in society. Much recent academic and journalistic commentary has drawn attention to the significance of emotion in the formulation of public and private opinion. Amongst other things, it has emphasised the divisive impacts on western societies of populism and collective violence. It has highlighted the disregard of legally grounded democratic principle by autocratic leaders and the nefarious practices of international corporations in the political and commercial manipulation of citizens’ feelings. For many liberal geopolitical commentators, ‘post truth’ has marked the decline, if not the death-throes of liberal democracy.

This awareness has not, however, inhibited the growing influence of ‘affect theory’ within social science itself. In fact, it may well have promoted it. As Ernst van Alphen and Tomáš Jirsa put it in the eloquent introduction to their edited text How to do things with Affect:

“When I hear the word affect I reach for my Taser. An unfair reflex, I know, but affect seems to me a prime medium of ideology today— an implanted emotionality that is worse—because more effective—than false consciousness”

Foster 2012 [1]

The comment was voiced live ten years ago by the art historian Hal Foster in a recorded roundtable on Art and Architecture. Van Alphen and Jirsa for their part were using it as a rhetorical counter-argument to their own polemical objective, namely to devise a method which enables ‘affect’ to be evaluated in ‘operational’ rather than primarily conceptual terms. In their words:

“Rather than providing definitions of what affects are (not), we find it more useful to focus on what precisely affects do, how they operate within aesthetic forms and cultural practices”

Van Alphen and Jirsa 2019:1 [2]

Evidently they were fed up with philosophical debates about the nature of emotion, its relationship to knowledge and understanding and the recent preoccupation with affect as a culturally constructed process. Their formulation chimes well with the goal of the SIG ‘Cultural Literacy and Social Change’. As probably overstated on the CLE website, the so-called ‘Culture SIG’ focuses on the link between cultural theory, literacy in the widest sense and tangible social outcomes. Whether you like it or not, ‘affect’ in its various iterations then presents itself alongside economics, politics and history as a core factor which cannot be overlooked: not simply because it has become modish in academic circles to turn to Deleuze and Guattari and others as an explanation of what has happened to Western Culture since the 1970s[3], but because the impact of the ‘affective turn’ has become such a palpably real aspect of mediated social behaviour. Its consequences are felt in different ways in different locations at different levels of society, but in almost all cases as an accessible response to widespread insecurity and uncertainty about the future.

In the face of overwhelming geo-political complexity and the apparent failure of the neo-liberal system to resolve global economic issues, one reaction on the part of social analysts has been to focus on the local rather than the global, to review the relationship between everyday life in community and the types of cultural activity likely to promote positive change at the micro-level through closely targeted research. Money is short. Practice-led research is under scrutiny. It remains the poor relation of fundamental, scientific investigation and the methodological principles which go with it. As is now widely acknowledged, the response from policy-makers is to encourage ‘co-participation’, viz. the active involvement of ‘ordinary people’ in socially grounded ‘research projects’, projects which raise the profile of their medium-term contribution to the ‘quality of life’ within and between the social groups of which they are part. Such a focus immediately raises questions about the relationship between the empirical observation of social practice and the theory which underpins it. If practice is to be ‘informed’ by theory, on which theoretical school should it draw? Or, to put the question differently, how should different theoretical approaches be most effectively combined in order to offer the most cogent blueprints for cultural action.

A fundamental axiom of ‘Affect Theory’ is that the attempt to drive an epistemological wedge between ‘emotion’ and ‘reason’ is not tenable in practice. As the pre-romantic, agnostic writers of the European Enlightenment amply demonstrated, cognition itself depends on sentient processes which link mind and body. By extension, relations between individuals and groups are themselves ‘embodied’ through the internalisation of shared experience. The recent extreme version of the latter principle underpinning affect theory holds that close intra-group associations are ‘pre-lingual’. Philosophically as well as physically, feeling precedes thought.

Logically, for non-believers in Freudian, Marxist or Behaviourist explanations, or indeed informed sceptics in general, the motivational essence which fuels the mechanisms of inter-personal dynamics escapes objective identification. It has to be felt before being ‘captured’ and thence communicated to others in symbolic terms, eventually to become collectively internalised as ethical, religious or ideological principles.

That symbolic ‘capture’ may be abstract and extremely sophisticated – witness the digital algorithms which structure communication within institutions, minutely categorise our behaviour and manipulate our collective emotional responses to experience. In everyday life on the other hand, the affective dimension is best manifested through language or, sociologically speaking, situated discourse whose ‘frames’ or ‘activity types’ operate as inter-modal cultural lenses combining music, physical performance, spatial architecture and material artefacts of all kinds. Following Deleuze and Guattari’s use of the term ‘agencement’, Slaby et al. refer to their conceptualisation of local relationality as ‘affective arrangement’:

“Affective arrangements are heterogeneous ensembles of diverse materials forming a local layout that operates as a dynamic formation, comprising persons, things, artifacts, spaces, discourses, behaviours, and expressions in a characteristic mode of composition and dynamic relatedness. Our approach facilitates microanalyses of affective relationality as it furthers both an understanding of the entities that coalesce locally to engender relational affect, and also the overall “feel,” affective tonality or atmosphere that prevails in such a locale. The proposed concept is an analytical tool—provisional and open-textured yet sufficiently determinate—to help researchers get a grip on complex inter- or intra-actional settings in which affect looms large.”

Slaby, Mühlhoff and Wüschner 2017:2[3]

However, from Rousseau through Vygotsky and Piaget to Froebel, Schutz and beyond, it is clear that ‘affect’ is much more than a state of mind. While in strictly clinical or philosophical terms, it may be said to precede action or even rational thought, once engaged, it becomes ‘activity-led’. Ideally, affect and activity enter into a virtuous circle which by definition extends beyond the individual, one in which group interaction is necessarily involved. It follows that the first challenge confronting the would-be ‘ethnographer of affect’ is to identify the salient everyday activities which constitute the ‘cultural glue’ of communities and closely to examine the processes by which these are symbolised and collectively represented. To that extent, the development of cultural literacy on the part of citizens and researchers alike becomes an exercise in social geography, designed to reveal the affective chemistry of belonging. The attempt to define this chemistry in national terms very quickly leads to stereotypes which for far too long have afflicted the study of intercultural communication. One striking aspect of pluralistic social fragmentation is that the insignia of ‘affective salience’ filtered through language and behaviour are increasingly context-specific and local in character. They need to be understood accordingly, on their own terms and in relation to each other by using the same heuristic instruments across the local board.Most of the above is blindingly obvious in principle. The problem comes when seeking to apply it in practice, most especially in finding ways to identify and evaluate the affective determinants of social connectedness in terms which are meaningfully communicable and theoretically coherent. All too frequently, the impressionistic, meta-discursive store of hyperbolic adjectives and fanciful metaphor quickly runs dry, to the point where in extreme cases the self-referential, reflexive style of affective analysis runs the danger of defeating its own object by simply replicating itself. Which is why of course, data and creative artefacts relevant to capturing the affective forces which bind and separate groups in society should emanate authentically from the voices of real people interacting in real-life situations. Such a move inevitably changes the role of the soi-disant ‘researcher’ who then becomes a creative yet critically responsible facilitator or mediator who gives meaningful voice to others rather than a scientist seeking empirically to demonstrate an anticipated truth. Thereby, researchers are agents in a catalytic process which enables cultural literacy to define itself.

The epistemological challenge which this discursive double-bind represents for researchers is addressed head on by the exploratory work of the Collaborative Research Centre (SFB 1171) Affective Societies at the Freie Universität Berlin. In fact, the main object of this blog is to draw colleagues’ attention to the clarity of exposition brought to the Centre’s on-line publications. Not only do the group’s outputs retrace the historical development of the relationship between thought and emotion derived from the work of Spinoza, Nietsche, Bergson and latterly Deleuze and Guattari, Nancy Fraser, Judith Butler, Sarah Ahmed, Brian Massumi and others; they also consider in a series of essays the impact of their legacy on current political culture.

The Berlin Group’s collective goal is to illustrate what is meant by the phrase ‘affective relationality’ when it is translated into real-life contemporary examples. It addresses such questions as the extent to which it is possible to reconcile antagonisms within and between specific social groups. As the quotation above illustrates, it highlights the need to identify material environments which foster ‘agencement’, that is sites where dynamic, embodied expressions of feeling can lead to new and sustainable affective formations: not of course for their own sake but as part of a network of activities involving different agents whose diverse outlooks and interests within a bounded local environment are complementary to each other in economic as well as in civic terms. Profuse examples of this kind exist in highly diverse contexts, despite the setbacks of the last two years. They should be identified, critically mediated and their ingredients more widely disseminated by independent research associations such as CLE so that their social and cultural benefits can be shared. I hope that the different case studies coordinated by members of this Special Interest Group will go some way towards meeting that objective.

Robert Crawshaw, 6th April 2022

References

See below a small sample of recent papers on ‘Affect’ published by members of The Collaborative Research Centre (SFB) 1171 ‘Affective Societies’ at the Freie Universität Berlin, funded by the German Research Foundation/Deutsche Forschungs Gemeinschaft (DFG). The papers can be accessed directly by clicking on the titles.

| The Politics of Affective Societies. An Interdisciplinary Essay – Hauke Lehmann, Jonas Bens, Gabriel Scheidecker, Gerhard Thonhauser, M. Ragıp Zık, Aletta Diefenbach, Dina Wahba. |

| Introduction: Affective Societies – Key Concepts – Jan Slaby. |

| Relational Affect: Perspectives from Philosophy and Cultural Studies – Jan Slaby. |

| Emotion, emotion concept – Christian von Scheve, Jan Slaby. |

[2] https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004397712_002

[3] Gilles DELEUZE and Félix GUATTARI L’Anti-Œdipe: Capitalisme et Schizophrénie (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 1972/1995)

[4] Jan SLABY, Rainer MÜHLHOFF and Philipp WÜSCHNER ‘Affective Arrangements’ in Emotion Review, 2017 p.2

Museums, Legacy, Art, Culture and Community

‘Revealed Roots, Concealed Communities’

A project in hand

Public on-line reports of the last ten years on the function of museums in society make interesting reading. They reveal a shift in priorities which in an ideal world might normally have been expected to attract additional public funding. In reality, the opposite is true. Given the state of the UK economy post-Covid and the vagaries of Brexit, the contrast in style between past and present documentation reflects a welcome improvement in messaging but fails to illustrate detailed ways in which its recommendations can best be realised in practice. The present case study seeks in a small way to fill that gap. It offers a fascinating insight into the role played by creative artists in transforming the environments in which museums and local communities can interact and, in so doing, reveals the potential for museums to modify their own institutional cultures.

The 2013 briefing by the UK’s National Museum Directors Council (NMDC) emphasises the contribution made by museums to the national economy. Pride of place is given to tourism (‘The most important part of Britain’s Tourism Offering’), visitor numbers, secondary spending, job-creation, attraction of investment from alternative sources, the centrality of major national collections to the generation of ‘soft power’ and cultural reputation seen in national terms. Inevitably, the report relies heavily on the ‘jewels in the crown’, the majority of which are located in major metropolitan centres, while referring to iconic examples which embody regional identity and heritage. It pays lip-service to small regional initiatives and Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) which have achieved national prominence.

The contrast between the 2013 briefing and the latest NMDC on-line statement: ‘Museums Matter’ (2021) is striking. The executive summary of the more recent document makes no bones about the problems associated with cut-backs in funding. At the same time, it is balanced, economical and articulate in its acknowledgement of museums’ public responsibility as civic agencies:

‘Museums matter because they uniquely serve a public past, a public present, and a public yet to be born… [They] curate, acquire, conserve, engage… [Otherwise] collections and cumulative knowledge wither’

Museums Matter (2021)

The summary is upbeat about the sector’s ability to confront current realities, describing museums as ‘Cultural enterprises which have adapted quickly to reductions in public funding’. It recognises nevertheless that despite the investment derived from The National Lottery, Trusts and Foundations, Private Donors and Taxation, there has been an ‘erosion of expertise since 2016 and ‘reduced investment in the built fabric’, leading to an overall reduction in the quality of visitor experience. It is refreshingly open in asserting that businesses only invest in ‘attractive and creative environments with a strong civic infrastructure’ and hence in the vital importance of ‘making a place attractive to live in’. Museums are ‘one of the few genuinely egalitarian civic spaces […]; a common treasury for all’, ones which offer ‘the opportunity to actively engage groups in their communities and ensure that their stories are documented’.

The report goes on to stress museums’ potential contribution to health and well-being: reducing levels of loneliness through collaboration with local authorities, hospitals and social care agencies, as well as the need for their closer integration into education through such imaginative interactions as object-based teaching, dramatic performance and staff exchange as part of programmes of lifelong learning. All this, combined with a review of technical innovation allowing for virtual tours, games, artworks and crafts created in collaboration with local institutions as well as linkages with associated artefacts from different environments across the world. The document concludes with a comprehensive wheel chart plotting the many ways in which museums can match their activities with the potential sources of funding available. All in all, it is a most impressive text which, unlike many of its kind, does huge credit to its authors.

If there is a drawback to the NMDC’s latest offering, it is certainly not in its articulacy format or coverage. It is simply that it has little space available to provide in-depth studies of individual experimentation. While it paints a comprehensive picture of the roles which museums should ideally play within society in general, it makes few recommendations as to how these can be promoted on the ground. Neither does it offer fresh suggestions as to how future initiatives should be funded, or, if they are, how they should best be sustained. In the current climate, both are of critical importance if the role of museums in communities is to thrive, not simply in the national context as income generators, but as creative hubs to promote cultural renewal, knowledge, understanding and a richer quality of life. The other comment which could be made is the inevitable consequence of a polemical overview. The overall message is clear: ‘Museums Matter’. The document makes its case supremely well but in covering all the bases, it is hard to differentiate adequately between the distinctive types of museum, their regional and local specificities and the particular character of the communities which they represent. Clearly museums do matter – they need to get real but how and for whom?

Which is where artists have a special role to play. Frequently employed on commission as curator-designers of exhibitions whose material contents and thematic focus have already been determined, there is now an increasing potential for them to fulfil a more inspirational function: that of redesigning the institutional structure of the museum itself, spatially, conceptually, inter-personally and in terms of the mobilisation of its human resources. The story of ‘Revealed Roots, Concealed Communities’ offers a practical insight into how this can be achieved cost-effectively. As a project, it is rich in ingredients for future development. The exciting creative idea behind Pippa Hale’s proposal to Rotherham’s Municipal Council was its originality. Why not invite the staff of the museum itself to curate their own exhibition? Instead of relying on professionally trained in-house curators, recruit front of office colleagues who would not normally be responsible for aesthetic decisions to generate ideas which correspond to their own interests as inhabitants of Rotherham. Enable citizens to speak for themselves. It would be for them to imagine new, colourful ways in which their personal interests could be represented as symbolic of local character and, in so doing, to generate more deep-seated patterns of social behaviour: in short to make a meaningful contribution to inhabitants’ cultural literacy.

How they did this – with Pippa’s help and the full support of the Council – is for them to describe: https://pippahale.com/portfolio/revealed-roots-concealed-connections/. Their account opens the door to future opportunities for sustainable collaboration between museums and local communities which this case study, in the citizen-curators’ own words, will seek to explore further.

Robert Crawshaw

3rd August 2021

www.robertcrawshaw.com

For Better or Worse: Socially Engaged Practices

Guest Blog by Anthony Schrag

www.anthonyschrag.com

Over the past few decades, there has been a growing interest in participatory processes. There is now a “necessity of ‘civil society’ participation in decision-making processes” (Saurugger, 2010). The realm of culture has not escaped this “participatory turn” (Bishop, 2012). ‘Socially Engaged Practices’ occupy a central place within the sector. Major cultural expressions in the form of exhibitions, projects, festivals etc. become mechanisms designed to integrate the cultural sector into different domains such as education, social work, health and so on. Problematically, this work often involves the expectation that the outcome will be ‘transformative’, where ‘transformative’ is often assumed to mean ‘making better’, without first having analysed who is defining this ‘better’ and on what terms?

This problem with the notion of ‘transformation’ is an ethical one. What are the real goals of artists (and arts organisations)? What objectives inform their relationship with the participants involved in their projects? What does the term mean for them? Participants have their own goals, politics and desires. They are not inert materials which can be shaped and moulded like clay or paint. Sophie Hope’s brilliant PhD Participating In The Wrong Way (2012) brings this problem into relief by highlighting the fact that funded participation projects often focus on communities which are elderly, socio-economically deprived, non-white, women, or criminal. What does it mean to try and make these constituent communities ‘better’? And what are the underlying assumptions about these people’s identities and their role in the world?

Hope’s work highlights the way in which assumptions such those described above are often reductive when defined as ‘democratic’. Hers is one of a litany of voices that challenge the instrumentalisation of artistic practice; her study The Cultural Policy Collective (2004) claimed that transformational programmes were indicative of a “growing crisis of democratic legitimation and social justice”. More recently, Hewitt (2011) argued that artists were being positioned as “service providers” to a welfare state that was to-all-intents-and-purposes a “distortion of the public sphere”, while Vickery (2007) stated that such work was being utilised to “construct civic identities” amenable to a state.

The critique of commentaries such as these has become more rather than less relevant, even if Covid 19 has put its potency provisionally on hold. While responsibility for distorting the function of artistic practice is based squarely on the shoulders of governments and cultural institutions, artists themselves are not innocent of bending policy to their own ends, if only to secure their own material survival.

I would not want this blog to become a polemic for socially engaged practices to be more ‘political’ and driven by the missionary zeal of building a leftist utopia: no, this too would be an equally problematic form of instrumentalisation, one which would leave little space for complicated narratives and the pluralistic nature of the public domain.

I call this my “Grandmother Problem”. My Grandmother (all 4 foot 9 of her; hair permed like the Queen) would have thrown herself in front of a bus if she knew that it would mean I would be safe. She was also a staunch conservative, and deeply capitalist. Most art activists would have written her off as ‘wrong-headed’, rather than someone who just had a different idea of how to make the world ‘better’. Socially engaged practice shouldn’t play politics by trying to create an alternative exclusionary utopia.

Instead, I call on practitioners in this field to reflect on the intentions and functions of ‘participatory work’ and to consider the answer given by artist Anne-Marie Copstake when asked “Whom do you work with?”. She answered: “I work with people who are not me”. Her response reveals the radical dimension of participatory practices: to meet and interact with those who hold different political concepts, who speak to different priorities and have other ideas of how to make the world ‘better’. To participate with such people is not to eradicate their beliefs and replace them with our own: rather it means to explore how we exist together.

This is not about creating consensus: rather it is about ensuring dissensus. As Rosalind Deutsche (1996) argues: “Conflict, division, and instability […] do not ruin the democratic public sphere; they are conditions of its existence”. The work of socially engaged practices, therefore, is to advocate for the democratic sphere by ensuring a multiplicity of perspectives: including – and especially – those different from our own, and not to use the practice to transform others according to our own image. To ‘transform’ after all, can also mean ‘to make worse’.

Changing Tack

Guest Blog in association with Artist Hannah Fox

I grew up in the 1970’s ‘on the road’ with the legendary collective of artists Welfare State International, a wild and evolving band of musicians, performers, dancers, pyrotechnicians, sculptors and writers. We lived in caravans and toured the World making work in communities, creating art and wonder, giving, teaching and usually leaving behind a creative impact in the places we visited.

Since then, for 30 years, I have been a professional freelance Artist undertaking my own work; making films, digital animations, projections, theatre shows, installations and constructions, all in a public context. I am asked into settings; a community, a landscape or a conundrum that needs an artistic response, process and outcome and I utilise whatever art form best suits the idea, the place, the purpose and the budget.

Image Credit: Ged Murray.

Reflecting on my recent past work I remember a project devised and undertaken with Kate Drummond in Paisley.

A close up, hands-on, socially engaged art work involving food, shared tables, intimate conversations and communal vinegar bottles.

Everything about this work seems an impossibility now;

The Fry-up

Over three days in March, 2019 we set up camp in Castelvecchi’s Fish & Chip shop in Paisley gathering true tales of adventure, love, life, loss and fish suppers from the cafe’s customers. In crisp white aprons we circulated around the tiny formica tables and slide in bench seats bringing tea, plates of chips and listening to tales told by the local customers visiting that lunchtime. All the stories where hastily noted down in our order books and then sifted and collated. We turned these stories into a newspaper – The Castelvecchi Chronicle. Hot off the press, the newspaper was then delivered back to the cafe for the classic ‘keep em warm and soak up the grease’ function. The wonderful proprieter, Alfredo Nutini, who made us welcome, made us chuckle and kept us well fed, wrapped the fresh daily orders at the Take-Away counter in The Castelvecchi Chronicle, to be taken home and read, warm and greasy, during supper.

We further presented our gathered work back in the chip shop one tea time delivering the ‘News of the Day’: a ten minute sketch show with an audience at the cafe tables. Everyone then tucked into a delicious poke of chips served up in the newspaper.

François Matarasso, artist, writer and researcher, author of ‘A Restless Art’ (London 2019) https://arestlessart.com writes about this project;

“On Saturday, the postman brought a copy of the Castelvecchi Chronicle, a newspaper of goings on, in and around a fish and chip shop in Paisley. It’s a delight. Little stories from customers, organised under rubrics such as “Lost and Found’, ‘Good News!’ and ‘Wish of the Day’. Glimpses of life, change, hopes and losses. The words were gathered over three days in March by Kate Drummond and Hannah Fox, who met in the 1990s at Glasgow School of Art. The newspaper – printed using food-safe inks – was used to wrap up fish suppers on a Thursday in late May and the artists performed a 10 minute news bulletin to the diners too. A simple idea, perfectly executed, complete unto itself. It’s what participatory art can be, at its best: quietly nourishing, like a good fish supper. “

https://arestlessart.com/2019/06/17/castelvecchi-chronicle/

The Film

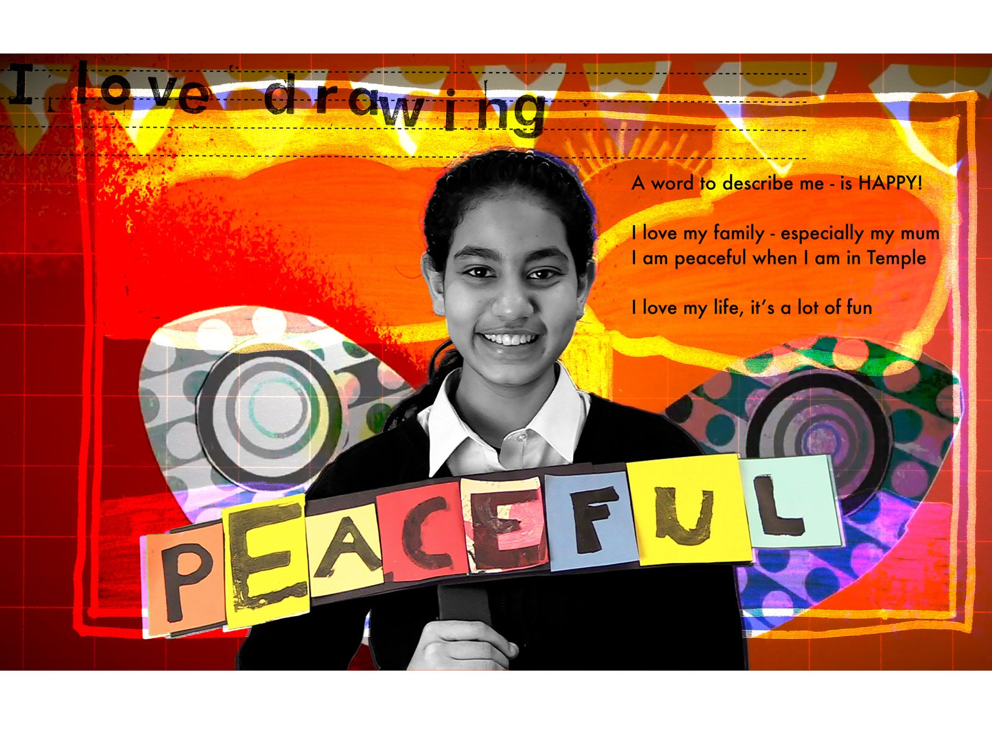

The Film, again in Paisley, again made in collaboration with Kate Drummond and this time also with spoken word Artist Cat Hepburn, was the first project of 2020 and the last pre-Covid,. It was the creation of a playful documentary film made with all the P7s at Gallowhill Primary School: The Gallowhill All Stars. This project required the essential, but now feared, human experiences of talking, playing, laughing and sharing:

Kate writes about it:

“It is a happy and humorous short film capturing a vital and transitional moment in the lives of these 2020 primary school leavers. The film celebrates each pupil’s identity and vision for their future. It was a joy to make. We had planned to have a ‘premiere’ with popcorn and a red carpet in the community centre – but this idea was scuppered by the lockdown.”

Work such as this screeched to an ugly halt at the onset of the pandemic.

Stunned for a while, I didn’t stand still for long;

The toad in the road which was Covid 19 and the lockdown months of 2020 were huge and disruptive but in many ways were another set of circumstances that I had to respond to. 30 years of freelancing means I take nothing for granted. No expectations of work arriving in a particular way or gigs being inevitable. Adaptability, imagination and resilience grown over decades of devising and delivering certainly served me well during the awful months that wiped out diary entries of projects that could no longer take place as planned. But from barren pages that briefly stopped me in my tracks, the same projects returned, this time needing to be rethought and reformed for the times we found ourselves in.

The Festival

I had planned to create an installation and community film at The Festival of Thrift, Redcar. Months of work leading to the September event, my build was to be a Cardboard Cinema open to welcoming hundreds of families over 3 days. Instead I created an alternative piece: an animated film accompanying the community choir anthem to open the newly invented digital Festival of Thrift.

The project was undertaken from my studio and sent via We Transfer.

The Fairytale

Due to create a rural touring theatre show with November Club in Northumberland from material developed in 2019, I headed to my studio and instead collaborated with the lead actor over several weeks at a distance of 300 miles. She against green screen and me directing and animating the worlds she existed in. The 5-part film, a hand-drawn adventure story of resilience and change, was taken on by several rural primary schools who were supporting isolated and battered children in lockdown in Northumberland.

The Fire Station

Having devised and facilitated workshops for Lakeland Arts across Cumbria early in 2020, in which communities created personal museums from paper, we kept the work safely in storage whilst seeking a new venue to exhibit in. Rather than the original Kendal Art Gallery, now closed to the public, we chose a beautiful drafty unused fire station in Windermere to show the work of 86 makers. “Museum of…” was safely visited by families over a month, one household at a time.

These projects and other digital conference contributions and design jobs meant a busy lockdown. All this output though, relied on experienced producers and commissioners who knew that the work must continue and that artists invariably bring creative solutions to overwhelming obstacles. Fundamentally they trusted me to adapt, consider the new context and come up with imaginative solutions. Good producers have moved swiftly with their thinking and have taken bold steps to find ways to keep delivering work to and with communities.

Working in the New Normal

In the dark months of Winter 2021, The Studio Morland, based in a tiny community in the Eden Valley, East Cumbria, reimagined their annual Festival of Light Light Up Morland. They commissioned me to make an online tutorial for the creation of hand-made lanterns. My considerations had to be how to create beautiful work from the kitchen table for free, with no resources or tools other than those already lying around at home and for others to enjoy during socially distanced night time walks. This was my response: Doorstep Lanterns

During the summer term of 2021 and with schools still under strict Covid measures, I devised and ran hands-on animation workshops from my studio live over Zoom for a month with Signal Film and Media based in Barrow-in-Furness. Four Cumbrian primary schools explored and celebrated the incredible archive of photographs of their area: The Sankey Family

Photography Collection, a priceless 70-year study of life, work and leisure in the North from 1900. The children, working in the classroom each on their own tablet, created moving and playful Digital Postcards, putting themselves into the scenes, to send as a gift and virtual ‘hello’ to the children in the other three isolated schools.

Adaptability has been my life boat during these troubling times. Changing tack, repeatedly, to navigate the rising tides and head o! the stormy challenges, happily not going under, has kept me and the work moving forward.

The door of my studio

https://www.instagram.com/hannahonthefoxhill/

https://www.facebook.com/hannah.fox.5203

link to blog article; https://cle.world/2020/07/30/holding-on-to-wonder/

‘Making sense’: An enquiry into the relationship between research, cultural literacy and citizenship

‘Is it possible that we cannot even define a specimen object-unit of a science of action without thus abandoning the role of observer and becoming a partner in a social relationship. […] If we become participants, do we lose our objectivity? If we remain mere observers, do we lose the very object of our science, namely the subjective meaning of the action? Is there any way out of this dilemma?[1]

It was in these terms that George Walsh’s magisterial 1967 review of Alfred Schutz’s 1932 phenomenological study of social science described the challenge which still faces the would-be sociologist or ethnographer in the exploded cultural environment of 2021. Can any student of culture justifiably claim that ‘their’ method of analysing a contemporary social issue is ‘value free’ (‘wertfrei’)? What is the scientific status of ‘evidence-based’ investigation into social behaviour? What is the relationship between subjectivity and objectivity? Between personal psychology and communal belonging or ‘citizenship’? Between those who consider themselves to be ‘culturally literate’ and others whom they believe to be less so? What does it mean, in any case, to be ‘culturally literate’? What ethical principle informs the relationship between the researcher and the researched, between those who create and those who take it on themselves to comment on the creativity of others? Between the colonisers and the colonised? Between atheists and the advocates of different religious creeds? Between people of different sexes? If ‘literacy’ is assumed to mean ‘the capacity to read’, what is ‘read-ability’ and to which category of object or creative action can the term be meaningfully applied? What does it mean to be ‘enlightened’ in a post-Enlightenment, post-colonial, corporately manipulated global culture which is politically divided and cripplingly unequal?

It is against the background of what Walsh refers to as this ‘unorganised manifold’[2] that the privileged position of the academically trained, post-Enlightenment, post-colonial, post-post-modern researcher has increasingly been called into question, leaving the field open to a multiplicity of viewpoints, built on a pluralistic ethos which struggles politically to accommodate socio-economic reality. This is not an attack on diversity. On the contrary, it simply underlines the fact that sociology’s claim to scientific validity is qualified at every turn by the situational construction of particular epistemologies, leaving little if any theoretical space for claims to transcendence. Michel Foucault himself confronted this paradox in 1970 in his celebrated inaugural address to the Collège de France. He acknowledged that his position in the pantheon of French scholarship was forcing him to claim transcendent authority for an open-ended, evolving theory of discourse which was itself based on the principle of reflexive, power-driven, political contingency[3].

The same challenge can be applied to current theories governing social science research methodology. Their relative shortcomings are made transparent by Schutz’s comprehensive analysis of the different factors involved in making sense of the qualities of mind that bind communities through grounded action or separate them from each other. There was only so far that he and his contemporaries could go in formulating a method capable of providing a reliable practical account of the conflicting tensions between ‘sense’ (Sinn): the feeling response of human beings to perceived reality, and ‘understanding’ (Verstehen): the cognitive operations which ‘made sense’ of humans’ perceptions in logical or rational terms. Neurological data, while physiologically valid in itself, was and still is of limited value when applied to culturally grounded facets of behaviour. While neuro-science has been the focus of psychological theory since at least the beginning of the 20th century in terms of the individual and has burgeoned of late, it is self-evident that the task becomes all the more challenging when dealing with collective ‘mindfulness’. The feasibility of pinning down and somehow measuring the process whereby individuals identify with the affective impulses which inform the perceptual processes of others is what Schutz refers to as ‘Fremdverstehen’, more recently verbalised as ‘inter-subjectivity’ and even more loosely as ‘empathy’. And then there are the further questions surrounding the links between shared feeling ‘in the moment’, the creative actions which express it, the deterministic forces of the context, the artefacts which emerge from them and the more durable symbols with which groups of different constitutions identify in different circumstances.

Phenomenological approaches which lend empirical status to shared emotion and identity are tested to destruction at moments of social fragmentation. The potential for the theorist and for the empirical researcher to ‘make sense’ of collective behaviour depends on there being a degree of stability in the way in which groups in society translate reality into symbolic terms. As industrialisation gave way to modernism, such abstract stability was a theoretical principle developed by de Saussure and applied empirically by Lévi-Strauss and the avatars of the structuralist movement. However, while universal as a principle, one of structuralism’s unfortunate consequences was that culture was all too easily characterised in national qua linguistic terms and had trouble dealing with the pragmatic reality of the everyday, especially that involving individuals and groups from mixed cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Another problem was the outsider status of the person responsible for ascribing meaning to the everyday life of another community. The capacity to ‘make sense’ of the relationship between routine behaviour and a superordinate ‘mythological’ structure vested in shared symbols: ‘read-ability’, was reserved for those with ‘educational capital’, thought by some, even now, to be collateral with the informed insight referred to as ‘cultural literacy’.

It was only with the demise of structuralism, leaving it to be superseded by the onslaught of postmodernism’s verbal, financial and symbolic liquidity that national cultural hegemony expressed in linguistic terms could be finally put to rest, though it has persisted long past its sell-by date. As Niklas Luhmann bluntly put it in 1997 ‘Es gibt kein letztes Wort’ (There’s no such thing as the last word)’[4]. As the polyphonic model developed by Bakhtin, and the theory of différance espoused by Derrida and Deleuze became more widely adopted in the West, sociological epistemology was to take a cultural turn. Affect theory, symbolic imagination, the growth of identity politics and the vagaries of academic fashion became the driving forces. Postmodernism was to insert a methodological wedge between a qualitative approach to cultural studies research and sociology’s established claim to scientific status. The counterpoint, as all of us recognise only too well, has been that the power of mathematical abstraction has hugely strengthened technology’s ability to model human behaviour and to analyse big data in quantitative terms.[5] It has followed that the pressure for qualitative sociological research to be rigorous in its procedures whilst remaining open-ended in the types of behaviour it is seeking to evaluate has, if anything, increased. As Crossick and Kazcinska put it, ‘data is not the plural of anecdote’.[6] It is this paradox which makes the incorporation of emotional iconicity into cultural studies research so hard to articulate in methodological terms: the challenge which affect theory has sought to meet over the last twenty years by drawing on the evidence of unsolicited public discourse[7].

All the above propositions place would-be project directors in the current cultural environment in the invidious position of ‘sense-maker’; they are taking on the role of ascribing meaning to the lived experience (Erlebnis) and actions (Handeln) of others, where ‘meaning’ is an incalculable amalgam of emotion and cognition at the individual level which is then extended through reiteration and symbolic translation into a shared property of culture. On the other hand, algorithmic modelling’s claim to be ‘scientific’ does not stand up to closer scrutiny when it comes to ascribing ‘meaning’ to human action. Rather It has the status of an instrumental hypothesis which can only be verified retrospectively in the light of human experience. According to this logic, it is inevitable that the social researcher be cast not as a scientist but rather as a mediator or facilitator whose task is to establish flexible, kaleidoscopic frames within which the expression of grounded experience and its translation into symbolic forms of representation become empirically representative of a given social reality. In the paradigmatic shadows of Michel Foucault and the versions of frame theory developed amongst others by Erwin Goffman and Deborah Tannen, it still remains the case that in the absence of mathematical models within which cultural collegiality can be tested (pace on-line dating and visual recognition software), a theoretical framework is discursively necessary for ‘good practice’ to be meaningfully identified and convincingly communicated to others (‘impact’). Recent experiential methodologies aimed at creating life-changing group experiences such as that exemplified by the work of François Matarasso[8], Brian Massumi and Erin Manning[9] and Dylan McGarry[10] offer ways forward whose mainstream application is work in progress. However, their sustainability in terms of lasting social change is still open to question.

To sum up the argument so far. A number of consequences have followed from the ‘de-objectivisation’ of cultural research. One is that the status of social philosophy and the hegemonic role of the trained researcher have been irreversibly undermined. The open acknowledgement that social research methodology is only as valid as the constructed status of the premise on which it is based has called into question the ethical position of the researcher and the extent of ‘their’ authority. Second, as revealed by the phenomenological investigations of the mid-20th century German school of philosophers and the modern-day avatars of affect theory, the factors causing individuals to identify with others is considerably more complex than the popular appeal to ‘empathy’ as a cultural catalyst would have us believe. Before becoming ‘cultural’, the experience of shared reality has to emerge over time as the outcome of co-creative action. Third, the speed and global outreach of mass communication fuelled by the power of international corporations have made the factual basis of scientific evidence very difficult to ascertain, making an alternative dialogic, dynamic approach more viable as a social diagnostic but challenging to achieve in practice.

Paradoxically, in the face of such uncertainties, it is hardly surprising that university based researchers and the institutions who support their projects should insist all the more strongly on the scientific rigour of their methods. Nor that in a cultural environment dominated by the need to promote collective ‘well-being’ against a background of crisis-ridden economic and cultural disparities, the shift towards qualitative research methods should become simultaneously more widespread and ethically fragile. It is this which makes the responsibility of ‘making sense’ less exclusive and, by extension, less credible when defined in strictly scientific terms. Weber and his followers, notably Henri Bergson, Husserl and Schutz himself, were aware that while the emotional components of shared cultural values were hard to reduce to scientifically verifiable categories, they could be ‘read’ (Bergson’s term) as reflections of experience embodied in material outputs and the symbolic representations with which they were associated. Identification with totemic archetypes on the part of participant actors would allow wider inferences to be drawn about the cultural context in which they had been created and the ‘moment in time’ to which they corresponded. The complex of factors inherent in the artefact would offer pointers or aesthetic indicators which could be ‘read’. The questions remain: by whom? how? and What action should follow?

To put these questions differently: what associations exist between the structure and content, verbal or material, of artefacts and the world of lived reality to which they correspond? And conversely, what is the dynamic which causes the artefact to attain the distilled status of symbol or ‘myth’ such that it becomes a cultural point of reference or localised ‘habitus’ with which people identify? These are hardly new questions. The process of interpreting the translation of artefact into socially significant symbol has been the subject matter of research by ethnographic trail-blazers such as Lévi-Strauss and the hermeneutic (‘philological’) method applied to literary text by German scholars such as Gadamer and Spitzer for whom a specific stylistic feature or ‘etymon’ could act as the microcosm of a cultural and historical environment. A more recent analogy of this approach has been Neil Macgregor’s encyclopaedic representation of world history through the informed analysis of emblematic objects in which insight and knowledge are necessary pre-requisites. As he memorably states in the introduction to his book based on his classic series on BBC Radio 4:

‘Can we ever really understand others? Perhaps, but only through feats of poetic imagination combined with knowledge rigorously acquired and ordered’ [11]

However, as we have seen, the difference between cultural historiography and the type of methodology required by ethno-cultural studies today is that the object of study reaches beyond the attributes of the object to creative acts which have become virtualised and infinitely diversified. This demands a more pluralistic source of data grounded in the act of creation combined with an awareness of its social significance which goes beyond the act itself. The insight and intuition which accompanies what Schutz called the ‘unit of action’ (see above) extends beyond enactment to an appreciation – a ‘making sense’ – of its qualitative contribution to its context. The capacity to ‘make sense’ of creative action in terms of its social value applies as much to the actor as to the observer participant, even if the discursive idiolect in which it is articulated is different. Is the sentient singularity (oneness) of an experience sufficient for it to qualify as ‘research’? Probably not, even if for the individual concerned it may be part of a process of self-discovery. Compare Aldous Huxley’s experiments with LSD with the excitement of participation in high risk sport or the collective trance or spiritual ecstasy experienced in religious ritual or at mass sporting or cultural events? The difference is surely that Huxley’s experiment involved agency and forethought, though whether it could be described as a ‘unit of action’ in the Weberian sense is at best debatable. Similarly, to be a ‘consumer of culture’ or ‘shopper’, while it may invite reflection on its socio-economic significance is hardly in itself a creative act. To be an actor researcher must arguably involve creative initiative. In addition, a degree of reflection is needed so that the experience can in some way be relativized and understood in comparative terms. What form this process should take is, however, another key question which still remains to be answered.

Before finally considering the link between ‘making-sense’ and ‘citizenship’ as an object of research, it is worth reminding ourselves of the forces which have highlighted the need for co-participation in project design and implementation. Much has to do with a culture of ‘sensibility’, readily promoted by the combination of corporate capitalism and popular media already alluded to; much too to population mobility, ethnic diversity, and economic crisis which have together highlighted the need to improve conditions of life in otherwise divided communities. A third factor, not yet fully explored, has been the blurring of the boundaries between art, nature and everyday life. The emphasis on creativity as an end in itself has created an intercultural space in which diversity of expression and its capacity to promote social change has become paramount but open to self-abuse by artists themselves. Creative art does not exist in its own aesthetic bubble. The distinctions between high and low art, performance and installation, film and technology, art, craft and the creative actions of the everyday have been revolutionised. It is this more than anything else which, while redefining the very nature of citizenship, has made it all the more important to create experimental situations in which the expression of local voices has material as well as symbolic status and to enable these voices themselves to define the parameters of project design.

It is for all the above reasons that ‘citizenship’, cultural literacy and social research methodology have become so intimately interdependent, in practical as much as in conceptual terms; why it is no longer acceptable for centres of higher education driven by policy-led, competitive ideologies to appropriate data from fieldwork for their own theory-led ends without there being reciprocal benefits for actors on the ground who share the power to control the durable application of research processes and outcomes. Co-participation in social research is a demonstration of ‘active citizenship’ which carries with it the civic entitlement to benefit from its findings. It supersedes the intellectual dichotomy which separates ‘making sense’ from ‘sense-making’: the traditional model in which ‘citizen-actors’ provide the data and ‘trained experts’ offer the analysis according to independent priorities. Instead, creative action arises out of collectively articulated local needs: co-action which ‘makes sense’ according to its own terms and sets its own standards. The initiators of such action become catalysts: de facto ‘citizen researchers’ who enable creative opportunities to attain the status of inter-active symbols with which local populations can identify in their everyday lives.

According to the terms of this research model, ‘cultural literacy’ is removed from the exclusive realm of critical understanding. Instead, it becomes absorbed into acts of participation which are meaningful to the participants and out of which knowledge is re-generated. In such a model, the trained researcher, like the artist, becomes a co-creator. In environments marked by ethnic and cultural diversity, ‘co-creation’ means joint activity which allows meaning to emerge organically through collective learning processes within secular spaces, where experiential knowledge understood in phenomenological terms is fused with practice informed by imagination. In such research environments, ‘trained researchers’ become cultural mediators or ‘entrepreneurs’ in the best sense of the word, in that their work is informed first and foremost by social interaction which ‘makes sense’ in terms of collective fulfilment. Only then can it become translated into imaginary constructs which are emblematic of the practices which they symbolise, which are communicable to other cultural contexts to be ‘read’ and practised accordingly.

[1] George Walsh ‘Introduction’ Alfred Schutz The Phenomenology of the Social World (London: Heinemann, 1972) p.xviii.

[2] ibid. p.xvi.

[3] Michel Foucault L’ordre du discours (Paris: Gallimard, 1971) pp.7-8.

[4] Niklas Luhmann Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft (Frankfurt: Surkamp, 1997) p.141

[5] Geoffrey Crossick and Patrycja Kaszinska Understanding the value of arts and culture (London: AHRC, 2016) pp.156-157.

[6] Ibid p.157.

[7] Robert Crawshaw ‘Beyond Emotion: Empathy, Social Contagion and Cultural Literacy’ Open Cultural Studies December 2018 2.1 pp. 676-685.

[8] Francois Matarasso A Restless art (London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2019).

[9] Brian Massumi Politics of Affect (Cambridge: Polity, 2015).

[10]Dylan McGarry ‘The Listening Train: A Collaborative, Connective Aesthetics Approach to Transgressive Social Learning’ Southern African Journal of Environmental Education Vol.31 2015 pp. 8-21. See also https://www.empatheatre.com/ .

[11] Neil MacGregor A History of the World in 100 objects (London: Allen Lane, 2010) p.xviii.

The renewed relevance of bricolage

One of the hapless outcomes of trying to define ‘cultural literacy’ in terms of social futures has been the need to understand the relationship between art, making, doing and their impact on society in a time of crisis. Practising art in the current climate barely puts food on the table, let alone changes society, unless artists and agents have access to patronage and space. Meantime, the entrepreneurial self-employed go bust, rental is a vicious circle, disadvantaged kids suffer from malnutrition and Netflix streams a slurry of fourth-rate screenplays and wooden performances sustained by corporate capital (witness the recent, mind-numbing remake of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca).

One critical option is to broaden the definition of authentic artistic practice. After all, ‘Art’ is creative doing, open to all, fuelled by ‘agency’, to the extent that people have the capacity to exercise it in their everyday lives. Notwithstanding Jacques Rancière’s idealistic attempt to inject sensibility into Fordist production processes, the aestheticism was his and surely not that of the young woman operatives he quotes from Vertov’s celebrated film The Man with the Camera (1929). For the actor/artist, art is not gratuitously mechanical. It demands a minimal degree of freedom and consciousness. It lies somewhere at the interface between personal impulse, context, the act itself and its social outcome. Under lockdown, art, action and artefact have become co-terminal. Critical reflection on creativity necessarily incorporates the politics of process.

Creativity in and of itself is not enough. In its essence, art may remain an inherent attribute of the subjective imagination. Yet it derives from a material base and leads to tangible outcomes, however provisional. If symbolism is social, ‘cultural literacy’ is ethnographic. Art does more than inform lived reality. It entails it as the translation of voluntary articulation with material systems, whether as the mass product of corporate interest, individual inspiration or the reflection of the day to day. To be aware of this principle and to enact it in everyday life as creator, employee or commentator is to be ‘culturally literate’.

Which is where the overworked concept of ‘bricolage’ re-emerges as a potentially intriguing catalyst. It is not just the fact that DIY and gardening have emerged post-Covid as two of the very few growth sectors in domestic consumption, limited like so much else to those who can afford plants, materials and a space to call ‘home’. Neither is this the place to engage in theoretical debate about the psychological development of the individual, except to say that now more than ever, with mental health dominating the media, the need for selfhood to re-engage with the real world through collective action has rarely been so great. Inextricably entwined as they are, well-being derives from plural perceptual processes reinforced by the symbolic translation of economic reality as much as from the sub-conscious impulses of individuals. Respect for diversity demands evidence of shared imagination grounded in experience.

The contemporary relevance of ‘bricolage’ as a cultural trope is admirably expressed in an inspiring paper by Christopher Johnson ‘Bricoleur and Bricolage: From Metaphor to Universal Concept’ published by Edinburgh University Press in the Journal Paragraph (2012) Vol.35/3. This finely written article, available on line, returns the reader to Claude Levi-Strauss’s original formulation of the term in La Pensée sauvage (1962) and convincingly demonstrates how and why it can inform current understanding of the dynamic relationship between art, creativity, society and technology. It raises wider questions concerning the interaction between individual sense-responses, shared emotions, everyday behaviour, identities, politics and the natural environment which go to the heart of what it means to be culturally challenged in a hyperreal world. These are issues which I hope to be able to pursue in subsequent blogs in dialogue with anyone who happens to have read this one.

Robert Crawshaw

November 26th 2020